The History of Encryption

Think about this: you’re living in ancient Egypt around 1900 BCE. Your pharaoh has just died, and you’re carving the inscriptions inside his tomb, but these are not ordinary hieroglyphs. You intentionally choose rare symbols, replace common signs with unusual ones, and even disrupt the normal reading order. Why would you do that? Because not everyone should be able to understand what is written.Congratulations, you just invented encryption.

Hieroglyphs

Ancient Egyptian scribes weren’t trying to create unbreakable codes. They just wanted to create a barrier. If you hadn’t spent years studying the weird variations of hieroglyphic writing, you simply couldn’t read certain texts. Royal stuff, religious secrets, tomb writings… these were for the educated elite, not regular people.

This is cryptography at its most basic form: controlling who gets to know what.

The method wasn’t secret. Anyone who saw the altered hieroglyphs knew something was different. But without the training, without being part of the inner circle, the message stayed a secret. Same reason you put a password on your phone today. We’re still playing the same game, just with different tools.

Spartan’s Secret Stick - The Scytale

As empires grew and wars got more complex, the stakes got way higher. An intercepted military message could mean the difference between winning and getting totally destroyed.

The Spartans came up with the scytale around 400 BCE. Imagine a wooden stick with a strip of leather wrapped around it. You write your message down the leather. Unwrap it, and the letters turn into random nonsense. But if you wrap it around another stick of the exact same thickness, boom… the message appears.

It’s extremely simple. The “key” is the physical dimensions of the rod. No rod of the right size? No message. Captured leather strip? Just random letters.

Super simple, right? The “key” is just the size of the stick. If you dont have the stick? You get to see no message. Even if someone steals your leather strip, they can’t read it without the right stick.

But the real game changer came from a Roman general who became emperor.

Julius Caesar’s Alphabet Trick

Julius Caesar had a problem. He needed to send military orders across huge distances, through areas where enemies might be lurking. Messengers could get caught, and messages could get read.

His solution? The Caesar Cipher (around 50 BCE).

The way it works it that you take every letter in your message and shift it by a fixed number of spots in the alphabet. Caesar usually used a shift of 3:

A → D

B → E

C → F

...

ATTACK AT DAWN → DWWDFN DW GDZQCrazy simple, amd insanely effective back then. This as due to that most people couldn’t read at all, and now even educated enemies who intercepted the message would see gibberish. Unless you knew the shift number (the “key”), you were stuck.

Here’s the cool part: Caesar could have kept his method secret. But he didn’t need to. Even if you knew he shifted letters, you’d still need to figure out by how many. You’d have to try all 25 options. Maybe totally doable, but not in a time when paper was rare and expensive.

But this also introduces a crucial principle that defines modern cryptography: the security is in the key, not the method.

The Pattern Breakers

As more people learned to read and got better at breaking codes, simple letter shifting became too easy to crack. Smart analysts noticed something: in any language, some letters show up way more than others. In English, you see ‘E’ everywhere, whereas ‘Q’ is super rare.

If you encrypt “ATTACK AT DAWN” with a basic substitution, the letter standing in for ‘A’ appears four times. An analyst sees this and thinks: hmm, probably ‘E’ or ‘A’. Keep going, and the whole thing starts unrevealing itself. This is called frequency analysis, and it was a powerful tool for codebreakers for centuries.

However, the Vigenère Cipher (1500s) tried to fix this. Instead of one shift, you use multiple shifts based on a keyword:

Message: ATTACK AT DAWN

Keyword: LEMONL EM ONLE (Based on the keyword "LEMON".)

Encrypted: LXFOPV EF RNHRYou repeat the keyword so it matches the message. Each keyword letter decides how much to shift the corresponding message letter.

Each letter shifts by a different amount based on the matching keyword letter (Repeated to match the message length). So the same letter in your message encrypts differently every time. ‘A’ might turn into ‘C’, then ‘T’, then ‘Y’. This way, pattern spotting gets way harder.

A + L (shift 11) = L

T + E (shift 4) = X

T + M (shift 12) = FFor hundreds of years, people called this “le chiffre indéchiffrable,” which is French for “the cipher you can’t crack.” They were wrong, but it was good enough to frustrate codebreakers for a long time.

World War II and the Enigma Machine

World War II changed everything. The Germans built Enigma, an encryption machine so advanced that it had 159 quintillion possible settings.

Think of a typewriter hooked up to a bunch of rotating wheels (rotors). You press ‘A’, and depending on how the rotors are positioned, maybe ‘Q’ would light up. But here’s where it gets interesting, because every time you press a key, the rotors also turn. So pressing ‘A’ again could yield ‘F’, hit it again and that would be ‘M’, one more time and you could get ‘W’, and so on.

The same letter never encrypts the same way twice in a row. So all that frequency analysis now becomes basically practically useless.

The Germans thought they had something unbreakable. But they were wrong too. Breaking Enigma needed some of the smartest people alive (including Alan Turing), stolen codebooks, German mistakes, and some early computers. It was a massive effort that probably shortened the war by years.

Enigma taught everyone something very important: complex machines don’t automatically mean strong security. The machine was fancy, but it had weaknesses. Given enough intercepted messages and enough computing power, it could be cracked.

The Single Key Problem

Modern computers changed cryptography forever. Suddenly, we could perform billions of calculations per second. We could test millions of potential keys. We could break systems that would have taken centuries by hand.

But computers also made something new possible: cryptography based on really hard math problems.

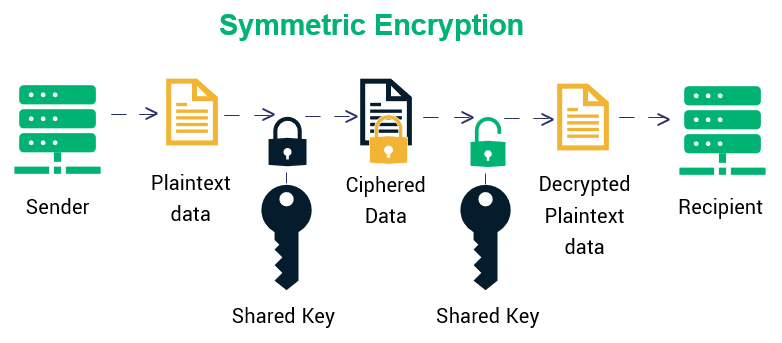

Symmetric Encryption

Modern symmetric encryption (like AES, the Advanced Encryption Standard) is basically a Caesar cipher on serious steroids.

Encrypt(message, secret_key)

Decrypt(encrypted_blob, secret_key) Both sender and receiver use the same key. This key isn’t a simple number such as a “shift by 3.” It’s typically 128, 192, or 256 bits of random data. And that’s not 256 possibilities. That’s 2^256 possibilities.

But Berkan, how big is 2^256 you might ask? Well to put that in perspective, there are estimated to be around 10^80 atoms in the observable universe. So even if every atom were a supercomputer trying one key per microsecond, it would still take an astronomically long time to brute-force all possible keys. In other words, it’s effectively impossible with current technology.

AES powers most of the encryption you use daily: encrypted files, VPNs, encrypted messaging, secure video calls. It’s fast, it’s strong, and it’s been brutally tested by the world’s best cryptographers.

But there’s a catch: How do you share that secret key securely in the first place?

If you’re in the same room, easy. Just whisper it. But what if you’re on opposite sides of the planet and never met? You can’t email the key because that email could get intercepted. You’re trying to set up a secure channel, but you need a secure channel in order to do it.

This is also known as the key distribution problem, and it has been a major challenge for cryptography for centuries. You can have the strongest encryption algorithm in the world, but if you can’t share the key securely, it becomes useless.

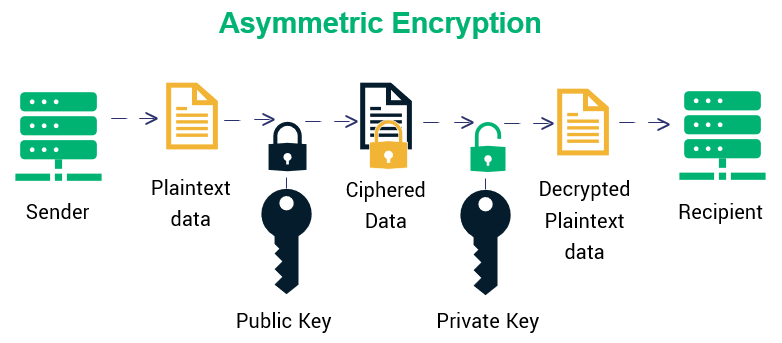

The Two Key Solution - Asymmetric Encryption

In 1976, two researchers named Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman published a paper that changed everything. They proposed an idea that seemed impossible:

What if you could agree on a secret key over a completely public, insecure channel?

This is asymmetric encryption, and it works because of a clever math trick.

Instead of one key, you get two:

- A public key that anyone can know

- A private key that only you know

Here’s the magic: Anything encrypted with your public key can only be decrypted with your private key. And vice versa.

Think of it like a special mailbox:

- Anyone can drop a letter in the slot (that’s your public key)

- But only you have the key to open it and read what’s inside (that’s your private key)

The most famous asymmetric system is RSA (named after Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman in 1977). It’s based on a simple fact: multiplying two large prime numbers is easy, but factoring the result back into those primes is really, really, REALLY hard.

Easy: 61 × 53 = 3233

Hard: 3233 = ? × ? (if you don't already know)If you scale the primes up to hundreds of digits, their product becomes astronomically large. Factoring that number with current classical technology is computationally infeasible.

In RSA, you generate two large secret primes p and q and multiply them to obtain a modulus n. The public key consists of this modulus n together with a public exponent e. The private key is a corresponding exponent d, which is mathematically derived using the two secret primes.

The security of RSA relies on the fact that while it is easy to multiply two large primes to create n, it is extremely difficult to reverse the process and factor n back into its original primes. Without those primes, an attacker cannot compute the private exponent and therefore cannot decrypt messages.

The mathematics guarantees that encryption and decryption work correctly, while the practical difficulty of factoring large numbers keeps the system secure.

This obviously solved the key sharing problem, as you now can post your public key on a website, shout it from a rooftop, spray paint it on a wall. Doesn’t matter. Without your private key, nobody can read those messages encrypted with your public key.

Hybrid Encryption - The Best of Both Worlds

Here’s the smart part: asymmetric encryption is slow. Like, hundreds or thousands of times slower than symmetric encryption. So we don’t use it to encrypt everything.

Instead, we mix them:

- Use asymmetric encryption to securely share a symmetric key

- Use that symmetric key to encrypt the actual data

When you visit an HTTPS website (indicated by the padlock icon), this is exactly what happens:

- Your browser and the server use asymmetric crypto to agree on a random session key

- All the actual data (images, text, videos) gets encrypted with fast symmetric crypto using that session key

- Next time you visit? New session key is generated

This way we get the best of both worlds. The security of asymmetric encryption for key exchange, and the speed of symmetric encryption for data transfer.

The Unchanging Constant

From Egyptian scribes to modern SSL certificates, cryptography has always had one constant thing: trust.

- Ancient Egypt: Trust that only trained scribes could read

- Caesar: Trust your messengers with the shift number

- Enigma: Trust your operators to follow procedures

- Modern crypto: Trust the mathematics, trust the implementation, trust that your private key stays private

The math got unbelievably complex. We went from “shift letters by 3” to “the discrete logarithm problem in elliptic curve groups over finite fields.”

But humans are still the weakest link. We reuse passwords, we click on phishing links, we store private keys unsecurely and we trust apps that we probably shouldn’t.

The ancient Egyptians knew something we’re still learning today: cryptography isn’t about making information perfectly secret. It’s about making it secret enough from the right people for the right amount of time.

Sometimes a “shift by 3” is enough.

Sometimes you need elliptic curves.

But you always have to ask yourself: Who am I trying to protect this information from?.

Quantum Threats and Post-Quantum Crypto

The story continues. Quantum computers threaten to break RSA and similar systems by solving those “hard” math problems much more efficiently. But the good news is that cryptographers are already working on post-quantum cryptography. These are new algorithms designed to be secure against quantum attacks, based on different mathematical problems that are believed to be resistant to quantum algorithms.

So all in all, the tools change, the math evolves and the threat landscape shifts.

But the fundamentals remains the same as it was in 1900 BCE:

I have information and I want only specific people to see it. Everyone else should fu*k off.

And this, is something we’ve gotten very good at over the last 4000 years. Just from the simple realization that information holds power, and power must be protected.